The Dutch Disease and Britain’s Path Forward: Lessons from the Netherlands’ Historical Stagnation

In recent analyses by the Institute of Economic Affairs and the Institute for Fiscal Studies, there is a discernible concern about the direction of public investment and economic strategy in the UK. To better understand our current challenges, it is instructive to look back at the Dutch Republic during its own period of decline, often cited as a classic example of what economists term the “Dutch Disease.” This historical perspective reveals important lessons that Britain can heed as it navigates its own economic future.

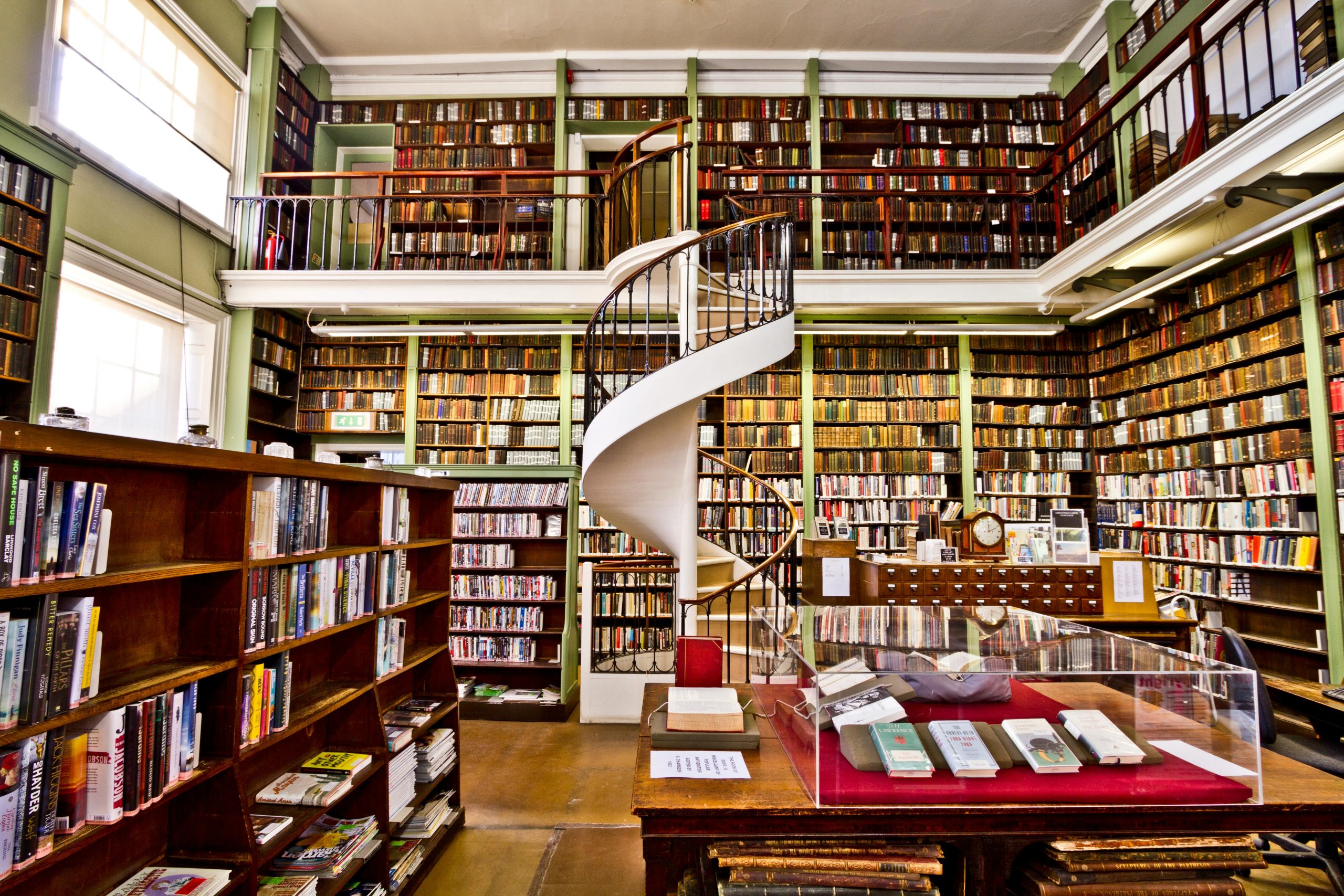

A Glimpse into the Golden Age of Amsterdam

Imagine Amsterdam in 1672: a bustling hub of commerce, where elegant merchant houses line winding canals funded by Europe’s most sophisticated financial system. The Dutch East India Company’s shares trade on the world’s first stock exchange, and Dutch banks finance monarchs and industrial ventures across Europe. Naval might at the height of its power, Dutch influence extends beyond trade, navigation, and finance to the very shape of global geopolitics.

This prominence, however, was ephemeral. A century later, the once-dynamic Dutch economy appeared to have entered a phase of elegant, but now sluggish, decline. The merchant houses remain, the canals still flow, but Dutch capital was increasingly flowing outwards—investing in British industry, Swedish mines, and foreign bonds—while domestic infrastructure languished. There was a discernible shift from innovation to rentier status, signaling a subtle but consequential transformation.

The Golden Age Trap: From Prosperity to Stagnation

The success that once propelled the Dutch Republic created conditions conducive to stagnation—a phenomenon we can term the “Golden Age Trap.” As wealth accumulated from global trade and financial ingenuity, domestic investment in infrastructure and innovation diminished. Capital capitalized on higher returns elsewhere; why invest in expensive Amsterdam factories when lucrative foreign opportunities beckoned?

This inward shift was rational: Dutch capitalists, acting as modern hedge funds, prioritized returns from foreign investments over reinvestment at home. Nonetheless, this prudence contributed to the decline of productive domestic capacity. Roads fell into disrepair, ports silted up, and educational institutions fell behind those of Britain and other rising powers. Politically, the decentralized Dutch system, originally designed to manage independent city-states and commerce, lacked the cohesion necessary for large-scale infrastructure projects.

Parallels with Contemporary Britain

Nations are sometimes undone not by scarcity, but by sudden abundance. The Netherlands discovered vast reserves of natural gas in the 1960s, and with that discovery came what economists would later call “Dutch Disease”-a paradox in which resource wealth corrodes the wider economy. Britain, with its North Sea oil boom and financialisation since the 1980s, now faces eerily similar questions.

What is Dutch Disease?

- Definition: When resource exports cause a country’s currency to appreciate, making manufacturing and other exports less competitive.

- Symptoms: Deindustrialisation, wage inflation in non-tradeable sectors, long-term stagnation.

- The Dutch Case: Gas riches funded welfare but hollowed out industry; when prices fell, the country found itself locked into slow growth.

The Netherlands’ Great Stagnation

From the 1970s onward, the Netherlands drifted:

- High wages, low productivity growth.

- Over-reliance on one sector.

- Complacency born of wealth. Even today, the term “polder model” reflects attempts to patch over structural weakness through consensus politics rather than radical reform.

Britain’s Parallel Story

Britain is not identical, but the rhyme is haunting:

- North Sea oil revenues underwrote tax cuts and welfare, while industry declined.

- Financial services dominance created a London-centric economy, vulnerable to global shocks.

- Regional inequality widened as manufacturing hubs hollowed out.

- Post-Brexit stagnation echoes the Netherlands’ sclerosis: high employment, but weak productivity, weak growth, and little innovation outside narrow sectors.

Lessons Britain Could Learn

- Don’t squander windfalls. Resource or financial booms must be invested in long-term capacity (education, infrastructure, R&D), not consumed.

- Avoid over-concentration. Healthy economies diversify-spreading risk across regions and sectors.

- Guard against complacency. Prosperity is fleeting without constant renewal; today’s London finance could be tomorrow’s dead gas field.

- Institutional reform matters. The Netherlands’ consensus model dulled dynamism; Britain’s adversarial politics prevents continuity of strategy.

A Forward-Looking Prescription

- A Sovereign Wealth Fund modelled on Norway’s could have preserved oil riches; the lesson is not too late for Britain’s future green or tech booms.

- Regional investment banks and manufacturing hubs could rebalance growth.

- A cultural shift from rent-seeking to risk-taking-from property speculation to productive enterprise-is vital.

Conclusion: The Parable of the Low Countries

The Dutch experience is not just a case study in economic textbooks. It is a mirror held up to Britain, warning of the dangers of easy money and the slow decay it brings. If Britain is to avoid its own “Great Stagnation,” it must treat resource and financial booms not as ends in themselves but as bridges to a more resilient, inventive future.

Insightful Analysis on Historical Lessons for Modern Britain

This comparison between the Dutch Golden Age and contemporary Britain offers a compelling reminder of how over-reliance on resource or financial wealth can lead to long-term stagnation if not balanced with sustained domestic investment and innovation. As a London resident, I see firsthand how our economic vitality depends on continuous reinvestment into infrastructure, education, and emerging industries.

Historically, the Dutch shift towards capitalizing on foreign opportunities at the expense of domestic growth highlights a crucial point: sustainable prosperity requires a balanced approach. For the UK, this suggests we should be cautious of systems that encourage rentier behaviors and prioritize financial gains over reinvestment in our own productive capacities.

Key lessons include:

By learning from history, especially from periods like the Dutch ‘Golden Age,’ Britain can aim for a more balanced and sustainable economic future that benefits all its constituents. It’s about striking that delicate balance between capitalizing on global opportunities and investing sufficiently at home to ensure long-term growth.

London's Reflection on the Dutch Disease and Britain's Economic Future

The historical insights into the Dutch Republic's decline offer valuable parallels for us here in London. The shift from a thriving, innovation-driven economy to one characterized by capital flight and stagnation underscores the importance of sustained domestic investment – not just in finance, but also in infrastructure, education, and technological innovation.

Given London's role as a global financial center, there's a risk that reliance on our financial sector could promote the "Golden Age Trap," where profits from international markets lead us to neglect the very investments that future-proof our economy. Balancing short-term gain with long-term resilience is essential.

Some lessons for us include:

By heeding these lessons from history, London can strive to avoid similar stagnation and sustain its position as a vibrant, forward-looking capital. It's about promoting a balanced approach that champions both our financial strengths and our capacity for domestic innovation and growth.